Price Tower Arts Center and its community are already proven magnets for those who appreciate architecture. Bartlesville is home to significant buildings by Welton Becket, Edward Buehler Delk, John Duncan Forsyth, Bruce Goff, HOK (Hellmuth, Obata + Kassabaum), Clifford May, and Frank Lloyd Wright, forming an impressive survey of aspects of 20th-century American architecture.

Price Tower Arts Center and its community are already proven magnets for those who appreciate architecture. Bartlesville is home to significant buildings by Welton Becket, Edward Buehler Delk, John Duncan Forsyth, Bruce Goff, HOK (Hellmuth, Obata + Kassabaum), Clifford May, and Frank Lloyd Wright, forming an impressive survey of aspects of 20th-century American architecture.

Contemporary design has not been neglected, with Price Tower Arts Center’s commissions from Wendy Evans Joseph and Zaha Hadid. The works of these architects, added to the Arts Center’s collections, provide an unparalleled architectural destination.

Neighboring Tulsa also enjoys a rich architectural legacy, with spectacularly preserved Art Deco structures that attest to the Oil Boom of the 1920s and 1930s. In Tulsa, Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Westhope (1929) for his cousin Richard Lloyd Jones, a local newspaper magnate. It is Wright’s only textile block house outside California. Joseph Siry’s account of architecture in early 20th-century Bartlesville is recommended reading (Anthony Alofsin, ed. Prairie Skyscraper: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Price Tower, New York, 2005, pp. 44-71).

Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright was born on June 8, 1867, in Richland Center, Wisconsin. He received his training at the University of Wisconsin, Madison and worked for J.L Silsbee and then Louis Sullivan in Chicago before beginning his independent practice of architecture in 1893.

The young architect’s first work was nominally a Silsbee commission –the Hillside Home School built for his aunts in 1888 near Spring Green, Wisconsin. While construction was underway on the Hillside Home School, Wright went to work for the Chicago firm of Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan, working as a draftsman on the Auditorium Building, which, at the time of completion in 1890, was the largest building in Chicago. He absorbed Sullivan’s influence and designed several houses, including one for himself in Oak Park, Illinois that was constructed with Sullivan’s financial assistance.

Wright’s architectural vision sought to link the individual to the environment. Wright’s prairie houses reflected this vision, with the use of long, low horizontal lines and native materials. Examples of Wright’s work during this period include the Robie House in Chicago, the Martin House in Buffalo, New York and Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois.

Wright’s architectural vision sought to link the individual to the environment. Wright’s prairie houses reflected this vision, with the use of long, low horizontal lines and native materials. Examples of Wright’s work during this period include the Robie House in Chicago, the Martin House in Buffalo, New York and Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois.

In 1909 Wright went to Europe and worked on two portfolios of his designs that would profoundly influence other architects and bring Wright international acclaim. In 1911 Wright returned to the United States and began building Taliesin, his home in Wisconsin. Although fire would damage Taliesin twice, each time Wright rebuilt the structure and continued to live and work there. During the 1930s Wright and his wife established a school for architecture students at Taliesin called the Taliesin Fellowship.

In the mid-1930s Wright designed the S.C. Johnson Wax Administration Building in Racine Wisconsin, Fallingwater in Pennsylvania and Jacobs I, the first of his Usonian homes that featured pre-fabricated walls, radiant heat, open floor plans and carports. He also designed a residence, Wingspread, near Racine for Herbert Johnson of the SC Johnson Wax company. His Usonian period, which was to denominate most of his career, comprised open plan structures that were theoretically inexpensive to build. It was Wright’s attempt to design a more “democratic” architecture for the American people.

The unforgiving Wisconsin winters spurred Wright to begin construction of Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona in 1937. This desert laboratory served Wright well for more than 20 years. He created and tested many design ideas at Taliesin West, and began working on plans for the Monona Terrace Civic Center in Madison, Wisconsin.

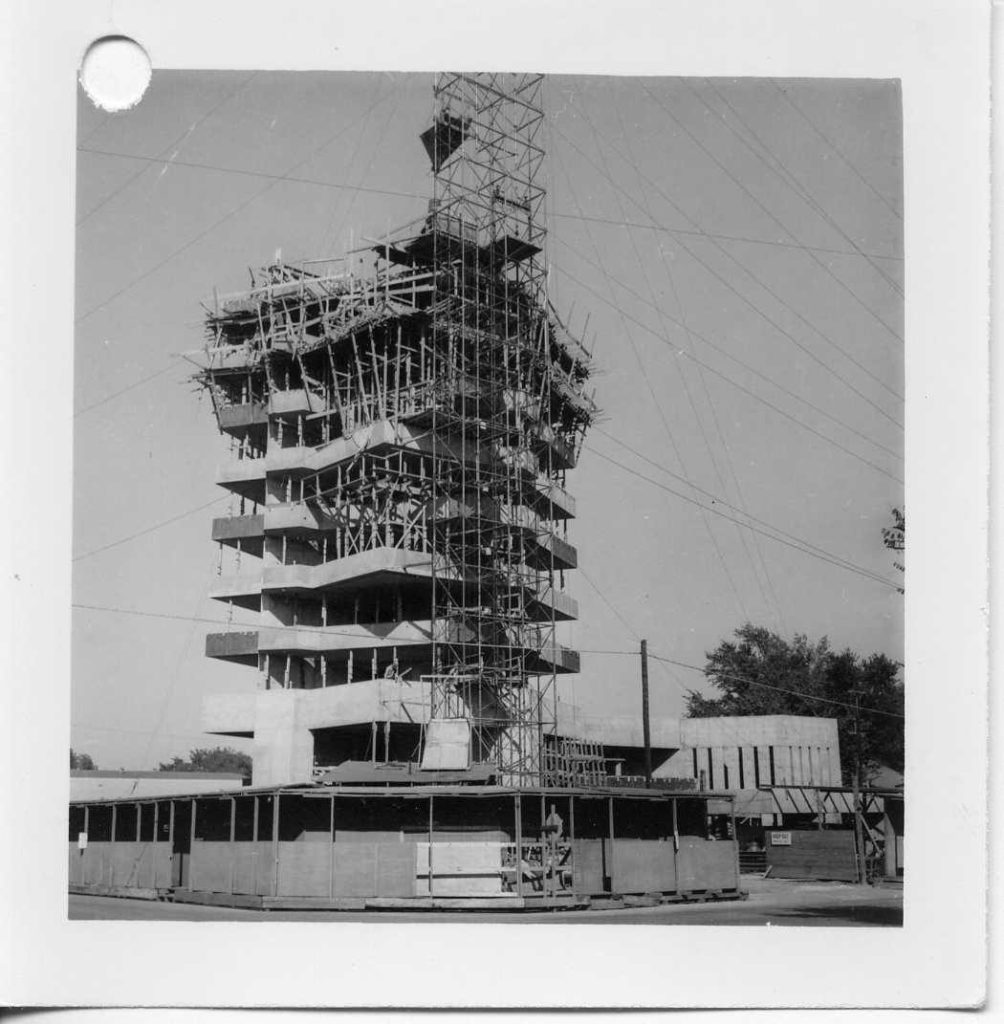

In 1943 Wright received a commission to design the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Ground was not broken for the museum until 1956 the year Price Tower was completed. During that same year, Wright wrote a book, The Story of the Tower documenting the Price Tower and its construction.

In August 1954 he completed the estate designed for Harold C. Price, Jr., Hillside, in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. Hillside is a large L-plan with a two-story living room. A balcony off the master bedroom overlooks this space. There is a separate, formal dining room and adjacent to it, perhaps Wright’s largest workspace. A hipped roof blends house and sky. The house went through considerable revision and an addition, a playroom by William Wesley Peters. From the original playroom to terrace doors is 114 feet of interior space; the unit module is a 3-foot square.

Wright designed more than 1100 projects during his lifetime and is regarded as one of America’s most influential architects. See Wright-related products available at the Wright Place Museum Store.

Wendy Evans Joseph

Acclaimed for projects such as the Greenporter Hotel and Spa on Long Island and The Women’s Museum: An Institute for the Future in Dallas, Wendy Evans Joseph has worked in dialogue with Frank Lloyd Wright’s distinctive spaces in the Price Tower, creating gracious and ample interiors that speak to his aesthetic yet have a distinct identity of their own.

John Duncan Forsyth

John Duncan Forsyth was born in 1886 in Florence, Italy. He received his training at Edinburgh College, Scotland, and at the Sorbonne, in Paris, France. He practiced in Tulsa and the surrounding areas from 1925 until his death in 1963.

Read More about John Duncan Forsyth

Bruce Alonzo Goff

Bruce Alonzo Goff was born in Alton, Kansas in 1904. Goff was to become a prolific architect, artist, composer, and educator. He spent most of his childhood traveling the Midwest, then at age eleven his family settled in Tulsa, Oklahoma. His father recognized his son’s immense talent for drawing, and arranged for him to apprentice with the firm of Rush, Endacott and Rush of Tulsa. In 1929, Goff was made a partner.

Read More about Bruce Alonza Goff

Zaha Hadid

Zaha Hadid was one of the leading international architects in today’s modern architecture. In a male-dominated profession, Hadid was one of the most well-respected women in the field. Based in London, where she was educated at the Architectural Association, Hadid became a partner of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture with OMA collaborators Rem Koolhaas and Elia Zenghelis.

William Wesley Peters

William Wesley Peters was born June 12, 1912 in Terre Haute, Indiana to Clara Margredant Peters and newspaper editor Frederick Romer Peters. He attended Evansville College from 1927 to1930, then studied engineering at Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1930 to 1931. In 1932 he became Frank Lloyd Wright’s first apprentice, firmly establishing the Taliesin Fellowship.

Read More about William Wesley Peters

Tulsa Art Deco

Examples of Art Deco architecture can be found all around the city of Tulsa, Oklahoma. During the 1920s, Tulsans were enjoying the wealth of big oil and a building boom, and they wanted local architecture to reflect the modern, progressive city they called home. Art Deco was the popular style of that time. It began in Europe in 1925 and was soon spreading throughout the world.

Zigzag or 1920s style, Depression Era or PWA style, and Streamline Art Deco structures are all part of Tulsa’s current landscape:

Christ the King Church (1926), located at 16th and Quincy, is one of the best examples of Zigzag Art Deco. Opened in 1927, the church was designed by architect Barry Byrne of Chicago. Byrne was apprenticed to Frank Lloyd Wright from 1902-1907. Beveled piers accent the brick exterior of the church, with terra cotta ornamentation designed by Italian artist Alfonso Iannelli. IIannelli also designed the church’s stained glass windows. Church furniture in the sanctuary was designed by architect Bruce Goff.

Boston Avenue Methodist Church, opened in 1929, is one of the city’s most well known structures. Its stylized lines and curves are classic examples of Zigzag Art Deco. Art teacher Adah Robinson is credited with the initial design and Bruce Goff with the final plan. The church’s totally modern designs and symbols make it one of Tulsa’s most famous Art Deco structures. In January 1999 the Secretary of the Interior named the church a National Landmark.

The Public Service Company building (Arthur M. Atkinson, architect; Joseph R. Koberling, Jr., designer; 1929) at the corner of 6th and Main makes use of many Zigzag Art Deco characteristics. Now used as community office space, the building was a nod toward general acceptance of the Art Deco style in the city. Also, the Oklahoma Natural Gas building (Atkinson, 1928) at the corner of 7th and Boston is a limestone structure with a Zigzag motif. And the Philcade (1930; owned by Amoco) at the corner of 5th and Boston was designed by architect Leon Senter to compliment the nearby gothic design of the Philtower. Senter used terra cotta and wrought iron as expressions of Art Deco design on the building’s exterior. Inside, the structure contains an opulent lobby with custom-made chandeliers and gold leaf ceilings. The Philcade, financed by Waite Phillips, brother of oilman Frank Phillips, is on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Pythian building (1931) at 5th and Boulder is a three-story structure that Edward W. Saunders intended to be thirteen stories high. The Great Depression intervened, and work stopped at the third floor. The building, now mostly vacant, has terra cotta tiles in the Zigzag style both inside and out.

With the Great Depression came PWA Art Deco. The Public Works Administration, part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, provided construction jobs that included government and public buildings. The Tulsa Union Depot (Frederick Kershner, 1931) was built using Zigzag design features on a large scale to serve the needs of three different railroads in the Tulsa area. The depot was bought by the Williams Companies and restored as office space. The Tulsa State Fairground Pavilion (Leland Shumway, 1932), Daniel Webster High School (Atkinson, John Duncan Forsyth, William Wolaver and Raymond Kerr, 1938), Will Rogers High School (Atkinson, Koberling and Senter, 1939) and the Tulsa Fire Alarm Building (Kershner, 1931) are other examples of PWA Art Deco in Tulsa.

After the Great Depression, Streamline Art Deco became popular. The style emphasized speed and motion. Buildings were simple and paid homage to the automobile and the sea with travel and nautical designs. Many Streamline buildings and homes have been torn down, but several still exist in the Tulsa area. The Brookside neighborhood is largely Streamline Art Deco, notably the City Veterinary Hospital (Koeberling, 1942) and the S & J Oyster House (1945). The Tulsa Monument Company and Will Rogers Theater are other examples of Streamline Art Deco structures.

Art Deco tours of Tulsa can be found at the Tulsa Historical Society.